The NHS is bracing for yet another major disruption as thousands of resident doctors (formerly known as junior doctors) prepare to walk off the job for five full days starting Friday.

But beyond the picket lines and protest signs lies a deep disagreement — not just about money, but about how the money is being measured.

Doctors Demand More Money — But Are the Numbers Adding Up?

At the heart of this latest strike is a bold demand: a pay rise of over 29%, which could push some doctors’ basic salaries above £70,000 a year.

For the most experienced among them, that could mean an extra £20,000 compared to current wages.

Union leaders at the British Medical Association (BMA) argue that years of “pay erosion” have left doctors worse off, despite recent raises.

Since 2022, resident doctors have received average pay increases totaling 28.9%, including a 5.4% boost this year — one of the biggest jumps in the public sector.

Still, the BMA insists it’s not enough.

And to make their case, they’re using an inflation metric that’s raising eyebrows.

The Great Inflation Debate: RPI vs CPI

The BMA claims doctors are earning 21% less in real terms than they did in 2008, once inflation is taken into account.

But here’s the catch — they’re using the Retail Price Index (RPI) to make that claim.

Why does that matter? Because RPI has long been criticized for overstating inflation, so much so that it was officially downgraded as a national measure back in 2013.

Most economists and the Government now use Consumer Price Index (CPI) or CPIH (which includes housing costs) to track inflation.

When the Nuffield Trust crunched the numbers using CPI instead, they found doctors’ pay has actually fallen by just 4.7% since 2008.

And if you start the clock in 2015, it shows a 7.9% increase. Quite a different picture, depending on where and how you look.

Government Calls the Strikes Irresponsible

Health Secretary Wes Streeting hasn’t minced words, branding the strike as “shockingly irresponsible.”

He pointed out that after receiving nearly a 29% pay rise over three years, doctors should recognize that government funds are limited — and other NHS staff are also in need of fair pay.

“Resources are finite,” he told MPs. “I have a duty to make decisions in the interests of all NHS workers — especially the lower-paid staff who also work incredibly hard.”

BMA Defends Its Numbers — and Says RPI Reflects Real Life

The BMA, however, is sticking to its guns.

It argues that RPI is a better reflection of the real cost of living, especially for doctors burdened with over £100,000 in student debt.

That debt is linked to RPI, as are things like train fares, car taxes, and housing costs — all of which significantly impact early-career doctors who relocate frequently during training.

In their view, if doctors are charged using RPI, then their pay should be assessed by it too.

Are Doctors Really Worse Off? It Depends on the Measure

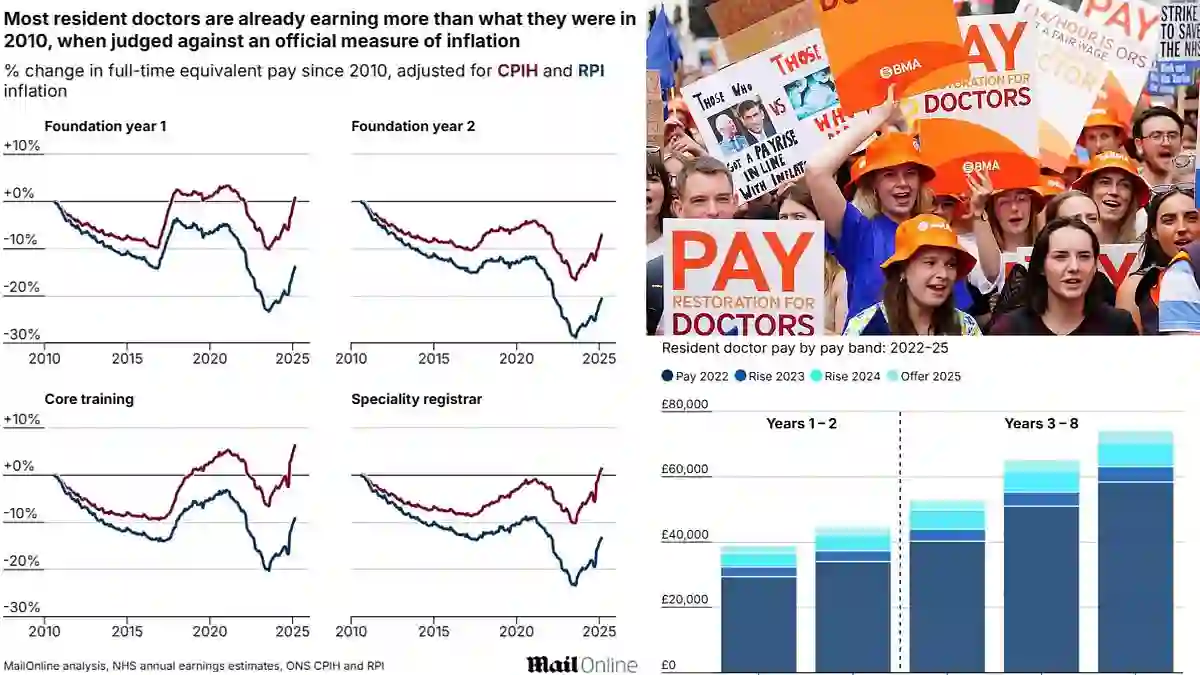

MailOnline’s own analysis reveals a mixed picture.

Looking at CPIH (which includes housing), most groups of resident doctors actually earned more in March 2025 than they did in August 2010.

-

FY1 (first-year) doctors: up 1.1%

-

Core training doctors: up 6.5%

-

Specialty registrars: up 1.7%

Only FY2 doctors showed a slight drop when comparing basic pay against inflation.

And these figures don’t even include overtime, night shifts, or bonuses — which typically make up a quarter of doctors’ total income.

Public Support Wanes as Doctors Vote to Strike Again

Despite a major pay deal last September — which offered 22.3% over two years — frustration among doctors hasn’t faded.

Nearly 90% of 30,000 BMA members voted in favor of new strike action this week, on a 55% turnout.

A government spokesperson responded, pointing out that resident doctors have had the biggest public-sector pay rises two years running, and yet a majority of doctors didn’t vote for these new strikes.

Why the Numbers Matter for Everyone

Health policy expert Lucina Rolewicz from the Nuffield Trust explains why this disagreement is so tricky.

“You can paint completely different pictures of doctors’ pay, depending on which baseline year you use and which inflation index you track.”

For example:

-

From 2008 using CPI, pay fell 4.7%

-

From 2008 using RPI, pay fell 17.9%

-

From 2015 using CPI, pay rose 7.9%

The choice of method drastically shifts the narrative — which is why the debate is so polarizing.

What’s the Cost of the Walkout?

While doctors demand fairer pay, NHS leaders are warning about the impact on patients and services.

A new report says the upcoming strike could lead to 250,000 cancelled appointments and cost the NHS £87 million in cover staffing.

Charities have voiced alarm, warning that patients could face “significant distress” as services stall.

Meanwhile, consultants standing in for junior doctors could charge as much as £2,504 per shift — funds that might otherwise go to essential services like new equipment, hospital repairs, or more procedures.

A Risk to Patients?

It’s not just about costs. An audit from a previous wave of junior doctor strikes found at least five patients died as a result of disrupted care.

NHS leaders now fear that the upcoming five-day strike could put even more lives at risk if no resolution is found soon.

So, What’s Next?

The government is reportedly considering student loan forgiveness as a way to ease tensions and prevent future walkouts.

But with both sides dug in — and very different views of what “fair pay” looks like — the standoff is far from over.

For now, hospitals are bracing for yet another round of disruption, while patients, doctors, and politicians anxiously wait to see who will blink first.