Years after the dust of the Iraq War has settled, newly released documents are shedding fresh light on just how determined President George W. Bush was to remove Saddam Hussein from power — and what really drove that decision.

It turns out, behind the public speeches and global posturing, there was a deep-rooted fear: that another 9/11-style attack could be just around the corner.

These revelations come from a batch of records declassified by the UK government and handed over to the National Archives in Kew — and they tell a sobering story about fear, conviction, and the consequences of acting on both.

Bush’s ‘Good vs Evil’ View of the World

According to private notes written by Sir Christopher Meyer, the UK’s ambassador to Washington at the time, President Bush was driven by what Meyer described as a “Manichean” view — meaning, in simple terms, that Bush saw the world in black and white: good versus evil.

In a report sent back to Downing Street in December 2002, Sir Christopher made it clear that the push for war in Iraq came primarily from Bush himself.

His biggest fear, Meyer wrote, was “another catastrophic terrorist attack on the homeland, especially one with an Iraqi connection.”

And for Bush, removing Saddam wasn’t just political strategy — it was personal.

He saw it as part of his mission to protect America by “ridding the world of evil-doers.”

Americans Backed Bush — Even If They Didn’t Want War

At the time, the American public wasn’t exactly eager to launch another war.

But according to the ambassador, they generally trusted Bush’s judgment on foreign policy.

He still had the country’s backing, even if the mood was cautious.

Sir Christopher believed that if Bush went ahead with the invasion in 2003 — which by the end of 2002 seemed almost certain — it would either define his presidency or destroy it.

Blair’s Hesitation and Push for Diplomacy

On the other side of the Atlantic, Tony Blair wasn’t so quick to jump in. At least not at first.

The newly released files suggest that Blair had reservations about going to war, especially since Saddam Hussein was insisting his regime had dismantled its weapons of mass destruction (WMDs).

In fact, Blair flew to Camp David in January 2003 to try to persuade Bush to give diplomacy more time.

But according to the ambassador’s report, the situation had already reached a point where pulling back from war — unless Saddam completely surrendered — was “politically impossible.”

Defence Officials Warned of Post-Invasion Chaos

While top leaders were focused on strategy and public support, officials in the UK’s Ministry of Defence were already sounding the alarm about what could follow an invasion.

The MOD warned of “significant levels of internecine violence” in Iraq after the fall of Saddam — a prediction that would sadly prove all too accurate in the years that followed.

Despite the warnings, the UK joined the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

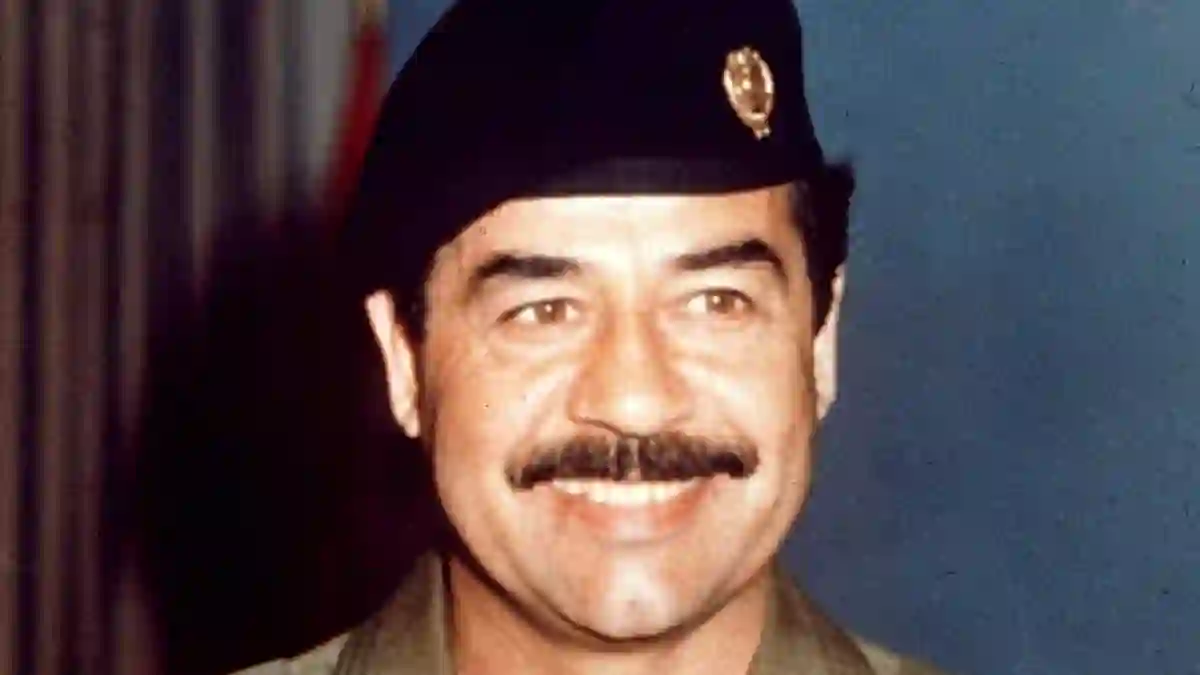

Saddam Hussein was removed from power, and one of the most iconic images of the war — Iraqis toppling his statue in Baghdad — was broadcast around the world.

Chilcot Inquiry Found No Justification for War

Years later, the war and its consequences were dissected in detail by the Chilcot Inquiry.

Led by Sir John Chilcot, the report concluded that Tony Blair’s case for invasion had been weak.

Saddam Hussein, the inquiry found, posed no imminent threat to the UK or its allies at the time.

Although Blair stood by his decision to go to war, he did acknowledge that “mistakes were made” — a statement many see as falling short of a full apology for a conflict that reshaped the Middle East and left a lasting scar on both UK and US foreign policy legacies.

What the Documents Tell Us About Power, Fear and Legacy

In the end, these newly declassified papers don’t change the outcome of the Iraq War — but they do offer deeper insight into the mindset of the leaders who drove it.

Bush, it seems, was haunted by the idea of history repeating itself.

Blair, for his part, tried to urge caution but ultimately followed America’s lead.

And while the war did remove a brutal dictator, it also unleashed years of conflict and instability that the world is still grappling with today.