What was supposed to be an exciting trip for a Philadelphia youth football team quickly turned into a legal nightmare when eight of their players were arrested for allegedly robbing a sporting goods store in Florida.

The incident has left their families, teammates, and fans in shock.

The Arrests That Stole the Spotlight

The young athletes, all aged 14 to 15 and part of the United Thoroughbreds team, were in Davenport, Florida, for the Prolifix Sportz National Championship against the Coco Tigers.

Instead of taking the field, they found themselves behind bars following a December 6 alleged theft at a Dick’s Sporting Goods store.

Polk County Sheriff Grady Judd didn’t hold back at a Monday press conference, making it clear that the teens’ alleged crime spree had consequences far beyond the store.

“I don’t know if these were starters or not, but we were finishers,” he said, highlighting that their arrests caused them to miss the championship game, which their team subsequently lost 26-6.

Florida Leadership Responds

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis joined in on social media, posting footage of the press conference on X and warning, “They picked the wrong state — and the wrong county.”

The governor used the opportunity to underscore the effectiveness of Florida’s justice system.

How the Theft Allegedly Happened

According to authorities, the teens allegedly stole 47 items worth over $2,200.

Sheriff Judd described the operation as systematic: the group reportedly split into two teams, with one teen buying an item legitimately while the others grabbed additional merchandise and stuffed it into a store bag.

“They stole, and they stole, and they stole,” Judd said, sharing details of hoodies, football gloves, and lip guards reportedly taken from the store.

Surveillance footage reportedly captured much of the theft in progress, despite the teens thinking they had gone undetected.

Coach Tries to Intervene

When the arrests happened at the store, the team’s coach rushed to the scene to plead with officers to let the players go. Sheriff Judd was not impressed.

“They were not taking bubble gum, one piece to chew. They stole over $2,000 worth of products, over 47 different products,” he said, emphasizing that the teens needed to face accountability.

Judd added that their actions affected the entire team.

“Not only did they steal, but ostensibly they may have cost their team the championship. They let the team down. What about the rest of the kids on the team?”

Legal Consequences and Next Steps

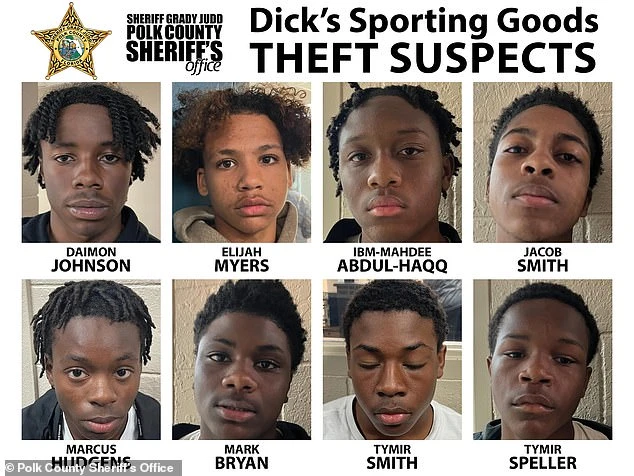

The eight teenagers—Daimon Johnson, Elijah Myers, Ibm-Mahdee Abdul-Haqq, Jacob Smith, Marcus Hudgens, Mark Bryan, Tymir Smith, and Tymir Speller—have no prior criminal records but now face two felony charges each: retail theft over $750 and conspiracy to commit retail theft.

Although released from custody, they must return to Florida to face the charges.

Sheriff Judd ended his message to the young alleged thieves with a sharp warning: “If you don’t steal, we’re your new best friends. If you steal, we’re your worst enemy. Merry Christmas.”

Share on Facebook «||» Share on Twitter «||» Share on Reddit «||» Share on LinkedIn